Breeding in Organic Farming

Principles and Methods

Breeds are adapted to local conditions (General Principle under 5.4, Breeds and Breeding, IFOAMs Norms 2012).

Breeding animals which are strong and robust and adapted to the local conditions is a strategy which is important both for health promotion and disease prevention. Traditional breeds of farm animals may be a good starting point for organic animal breeding. Animals can be improved by selection of individuals specially adapted to their natural organic conditions. They can be crossbred with suitable new breeds, thus achieving animals with the desired positive aspects of both breeds.

For breeding, organic farming uses natural reproduction techniques, keeping bulls at the farm for natural mating. Although artificial insemination is allowed, we do not promote AI Techniques but rather breeding systems based on the integrity of animals, which AI techniques do not respect.

Breeding in organic animal agriculture is based on the following requirements (IFOAM Norms, 2012): :

- 5.4.1 Breeding systems shall be based on breeds that can reproduce successfully under natural conditions without human involvement.

- 5.4.2 Artificial insemination is permitted

- 5.4.3 Embryo transfer techniques and cloning are prohibited.

- 5.4.4 Hormones are prohibited to induce ovulation and birth unless applied to individual animals for medical reasons and under veterinary supervision

Breeding Goals

Over the last decades, traditional breeds have been replaced by high performing ones in many regions. Similar to high yielding plant varieties, these new animal breeds usually depend on a rich diet (concentrates), a huge amount of water and optimal / protected living conditions, because they can be very susceptible to disease. It can be very expensive to keep such animals. Some of the conventiona lanimals are even bred from lines which grew up on a huge amount of veterinary treatments, which also contributes to less robust animals and dependency on veterinary inputs. When focusing only on one breeding goal such as high yield, we often lose other abilities, which have to do more with robustness.

As emphasized above, many organic farmers do not keep animals only for production, but also many other purposes and all of them should be considered in the breeding goals. Below, there is some inspiration to discuss: ‘what are the most suitable breeds for our farms?’

Is maximum performance or life production a relevant breeding goal in organic herds?

When comparing the production of different breeds of cows, the daily or yearly production or daily weight gain are used. However, high performing so-called ‘exotic’ breeds usually have a shorter life span than traditional breeds with lower production. The life time milk production of a cow which e.g. gives 8 litres per day over 10 years, therefore would be greater than the one of a high yielding cow which yields 16 litres per day, but is culled or dies after 4 years. It costs money and risks to raise an animal from newborn or newly hatched to a productive animal, and once it is ‘stabilized’ as adult, it is evident that it fits well into the particular environment.

Finally, having an animal for more years – e.g. a cow for 10 lactations – require a very good framework and care for the animal, and having this as a goal reflect such goals of giving the animals sufficient living conditions for living a long life. This is relevant to include in the breeding goals.

Below, a figure illustrates some factors which can be discussed in relation to priorities regarding breeding animals, and comparing breeds of cows.

Keeping animals outdoor and indoor

It is crucial to keep animals in ways which allow them to move freely, as emphasized in the IFOAMs Norms 2012 (5.1.3, page 43):

In particular, the operator shall ensure the following animal welfare conditions:

- (a) Sufficient free movement and opportunity to express normal patterns of behavior, such as space to stand naturally, lie down easily, turn around, groom themselves and assume all natural postures and movements such as stretching, perching and wing flapping;

- (b) Sufficient fresh air, water, feed and natural daylight to satisfy the needs of the animals;

- (c) Access to resting areas, shelter and protection from sunlight, temperature, rain, mud and wind adequate to reduce animal stress.

This applies both on indoor or outdoor keeping, and it is emphasized that this is also possible when tethering on grass. Specifically about outdoor keeping, according to IFOAMs Norms (2012; point 5.1.8) ‘All animals shall have unrestricted and daily access to pasture or a soil-based open-air exercise area or run, with vegetation, whenever the physiological condition of the animal, the weather and the state of the ground permit. Such areas may be partially covered. Animals may temporarily be kept indoors because of inclement weather, health condition, reproduction, specific handling requirements or at night. Lactation shall not be considered a valid condition for keeping animals indoor’.

In many smallholder tropical farming systems, this is difficult, and there are many ways of trying to solve this. It also says in the newest version of IFOAM’s Norms that ‘On holdings where, due to their geographical location and structural constraints, it is not possible to allow free movement of animals, tethering of animals may be allowed for a limited period of the year or of the day. In such cases, animals may not be able to turn around freely but other requirements of 5.1.3 must be fulfilled’.

The pros and cons for shed feeding versus grazing is discussed below in relation to feeding; this is an area where the integration of animals into the farm should be very carefully thought through, including how the different elements can support each other.

The IFOAM Norms (2012) also says that herd animals such as cows which always live in a group, must not be kept in isolation from other animals of same species, although acknowledging that this will not be possible in some smallholder farms where they e.g. only have one animal. In special cases, isolation is acceptable, such as when keeping males from females or in case of disease. If there is only one animal of a species on a farm, good human contact or contact with other animal species can help a lot.

Outdoor access as well as indoor housing conditions will be managed differently for different animal species and this will be specifically dealt with under each of the animal species.

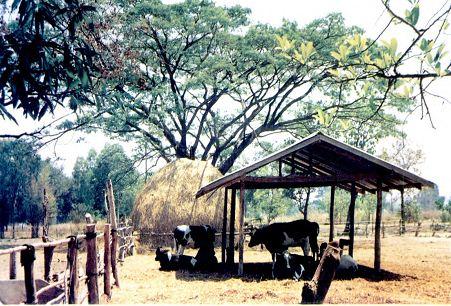

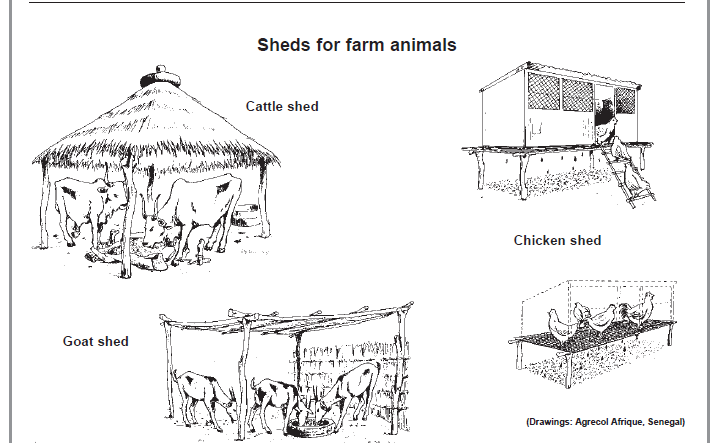

Indoor housing conditions

With the exception of nomadic lifestyles, most farm animals are temporarily kept in sheds. The combination of animal husbandry and other farm activities requires that the animals are kept under control to avoid damage to crops. As emphasized above, they should be allowed free movements (IFOAMs Norms 5.1.3). Furthermore the Norms point to need that the ‘building construction provides for insulation, heating, cooling and ventilation of the building, ensuring that air circulation, dust levels, temperature, relative air humidity, and gas concentrations are within levels that are not harmful to the livestock’. This includes the requirement that there should be sufficient aeration, but no draught. The Norms also say that ‘no animals shall be kept in closed cages’, and ‘animals are protected from predation by wild and feral animals’. Lastly, it is also emphasized that the amount of artificial light should be limited – this applies more for large industrialized farms than for most smallholders.

Hygiene must be emphasized: there should be as little contact as possible between the animals and their own manure, both for their own health and wellbeing, and for human health reasons.

IFOAMs norms say that construction material and production equipment that might significantly harm human or animal health shall not be used. Generally, the construction or equipment should not harm at all! For economic reasons, sheds can be built with simple, locally available materials. Many countries have a rich tradition of shed constructions, and have developed the most efficient and appropriate shed systems for the conditions of the region. If techniques of this heritage are combined with the above principles, a locally adapted and at the same time animal friendly system may be obtained.

Examples of sheds for different farm animal species are shown on the right side, and will be discussed in more detail under each animal species.

Bedding material

‘… where animals require bedding, adequate natural materials are provided. Bedding materials that are normally consumed by the animals shall be organic (IFOAMs Norms 2012, point 5.1.7 p. 45).‘

Bedding materials should be used in sheds to keep the lying area of the animals soft, dry, and clean. This is important for their health and wellbeing. The beddings need to be replaced from time to time, and can be used in the gardens as compost, which recycles nutrients to the plant and add improves the soil (which e.g. enhance its water retention capacity). Beddings can be of straw, leaves, twigs, husks or other locally available material. They can be replaced daily or kept for several months while adding fresh material on top, and letting the material in the ‘mat’ compost. (the mat is the mattress, if you apply material on top of other material without removing the old straw or leaves or whatever material you have before applying new. Then a ‘mat’ (e.g. a straw mat) or a ‘mattress’ is built up.)

Feeding animals

Organic animals receive their nutritional needs from organic forage and feed of good quality (IFOAM Norms, 2012; General Principle of Animal Nutrition, 5.6). Animals shall be offered a balanced diet that provides all of the nutritional needs of the animals in a form allowing them to exhibit their natural feeding and digestive behavior (IFOAM, 2012, 5.6.2),

Organic animal feeding should be mainly based on fodder produced on the farm, and this is an important aspect of the harmonic and well-balanced organic farming systems. According to IFOAM’s requirements, at least 50% of the feed must be from the farm or from other organic farmers in the area. The health and wellbeing of animals is strongly linked to the feeding. Fodder production should be integrated into the crops and other plant productions on the farm.

Organic animals must be fed organic feed – that means the feed is without pesticides and mineral fertilizer and as a part of a farming system which farm in accordance with the organic principles (not organically certified). Exceptions can be made if there is a very limited amount of organic feed in the area. From the farm itself, it is permitted to use feed produced on the farm as ‘organic feed’ to the farm’s own animals during the first year of organic management.

Support the health of animals with a well-balanced diet

It is important for all animals to have a well-balanced diet which meet their needs. A part from physiological maintenance, the dietary requirements of the animal will also depend on whether the animal is kept for milk, beef or draught power. Seen from an economical perspective, it will always make most sense to limit the number of animals and give them all sufficient feed, if limited resources are available.

Likewise, different animals require different amounts and composition of feed in different life situations. The details about this can be found under each animal species, and so are the signs of deficiencies and imbalances for each animal species.

Minimum Space and Water Consumption

Where livestock are housed, the minimum “on-ground” density for the indoor area shall be not more than the following:

| Type of animal | Minimum space per animal | Water consumption in litres/day per animal |

| Bovine and Equine (adults) Cattle/Donkey/Horse | 4.0 m2/animal | 30-80, donkeys and mules need twice a day 10-25 or as much as they can drink |

| Camels | – | daily 15-30 or every 5-8 days as much they can drink: up to 100 litres or 1/3 of bodyweight |

| Sheep and goats (adults) | 1.5 m2/animal | 5-20 |

| Porcine (pigs) (>40 kg) Sow with piglets | 1.0 m2/animal 3.0 m2/animal | 15-25 10-25 |

| Poultry (adults) chicken/duck/geese/turkey | 6.0 m2/animal | 0.5-0.75 |

| Rabbits | 0.3 m2/animal | 50-150 Millilitre per kg bodyweight |

Water should be available at all times (except for camels, they can do with water every 5-8 days) and be clean and fresh.

Remember that young animals also need water! Even when they are milk fed, it is not always fulfilling their needs for liquids, especially not if active and if it is warm or hot and dry, or maybe even windy.